Welcome to the first chapter of a three-part journey through the saga of injection molding—a tale of ingenuity, struggle, and triumph that reshaped manufacturing. In this installment, we explore its origins, from humble beginnings to the dawn of a new era.

Injection molding today shapes nearly every object you touch—from toothbrushes to automotive parts—but its roots aren’t exactly glamorous. In fact, they’re weirdly humble. Picture a pewter craftsman in 1834, candles dripping wax on his workshop floor. Little does he know, his simple idea of injecting hot wax into molds will ignite a manufacturing revolution.

From Candles to Rubber: The Birth of a Concept (1834–1849)

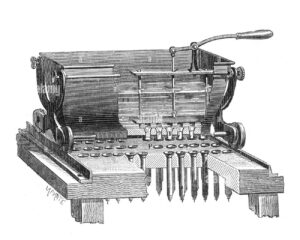

In 1834, Joseph Morgan, a British pewterer, invented a simple yet brilliant hand-plunger to force molten wax into candle molds. Morgan wasn’t dreaming big—he just wanted to speed things up. But unknowingly, he planted the seed for an industrial transformation.

Soon after, in 1846, Charles Hancock in London patented an injection machine for rubber—think boots and tires, not exactly high-tech, but crucial. Three years later, across the Atlantic, John A. Sturges developed a small metal injection machine for printer’s type, speeding up the tedious task of typesetting. Without realizing it, these innovators had laid the mechanical groundwork—heated barrels, plungers, molds—that would shape the future of plastics manufacturing.

Joseph Morgan’s wax injection apparatus

Explosive Innovation: Plastics Enter the Scene (1862–1869)

Injection molding needed just one thing: a versatile, moldable material. Enter Alexander Parkes in 1862, proudly showcasing “Parkesine,” the world’s first synthetic plastic, at the Great International Exhibition in London. It was exciting—yet brittle, flammable, and impractical. But the plastics race had begun.

The real breakthrough came in 1869, from an American inventor named John Wesley Hyatt. Inspired by a contest to replace ivory billiard balls (saving elephants from extinction in the process), Hyatt invented celluloid—the first practical thermoplastic. Moldable and tough, celluloid was revolutionary, but had one terrifying flaw: it was dangerously explosive. Undeterred, Hyatt envisioned a machine to tame this volatile plastic.

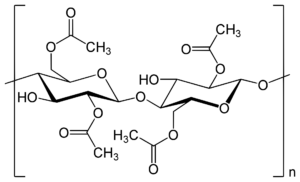

celluloid molecule chain

The World’s First Plastic Injection Molding Machine (1872)

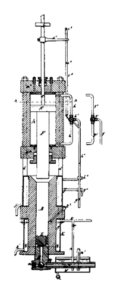

In 1872, John Hyatt and his brother Isaiah patented the world’s first plastic injection molding machine—a vertical, steam-heated beast that forced molten celluloid into metal molds. It looked like a giant hypodermic needle, injecting plastic instead of medicine. The Hyatt brothers quickly started molding billiard balls, dominos, and combs.

But reality soon hit hard: uneven heating, inconsistent results, and celluloid’s nasty habit of bursting into flames limited commercial success. Despite Hyatt’s brilliant machine, plastic molding briefly fell out of favor, replaced by simpler compression methods.

Hyatt/s brothers first IMM

Safer Plastics, Bolder Machines (1903–1926)

Plastics—and injection molding—needed safer materials to thrive. In 1903, Arthur Eichengrün in Germany introduced cellulose acetate, dramatically less flammable than celluloid. Around the same time, Leo Baekeland in New York developed Bakelite, the first fully synthetic plastic. Suddenly, plastics were safe, tough, and ready for mass production.

Eichengrün didn’t stop there. By 1919, he’d designed the first truly modern injection molding machine, kickstarting Germany’s molding industry. By the 1920s, companies like Eckert & Ziegler built horizontal, automatic injection presses—machines capable of consistent, repeatable production. In the U.S., Grote Industries launched fully automated molding machines, churning out plastic reflectors and road markers by the thousands. Injection molding was finally hitting its stride.

The 1930s: Hydraulic Power and New Plastics Change the Game

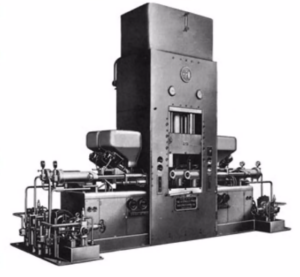

In 1930, injection molding took another huge leap. British engineer John Shaw introduced hydraulic power to injection machines, increasing pressure, consistency, and capacity dramatically. Machines that had once required careful manual control now operated swiftly, accurately, and powerfully.

Meanwhile, Fritz Gastrow in Germany solved another critical problem—uneven melting—by inventing the torpedo heating cylinder, making plastic flow smoother and faster into molds.

The plastics themselves evolved rapidly. Chemists in the 1930s introduced groundbreaking materials: polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA, known as acrylic), polyethylene (PE), and nylon. Suddenly, molders had an entire palette of robust, versatile plastics, perfect for mass production.

John Shaw hydraulic IMM

On the Brink of Greatness (1940)

As World War II loomed, the injection molding industry stood ready. Machines were more powerful, plastics safer and more versatile, and mass production a reality. Wartime demands—helmet liners, aircraft components, and countless everyday items—created immense urgency for rapid production. Injection molding was about to shift into overdrive.

Inventors, engineers, and industrial giants had built a foundation over a century, piece by piece. But the biggest revolution was just around the corner, and it would come from an entirely new concept: a rotating screw inside the molding machine.

No one knew it yet—but injection molding was about to change the world. Forever.

Just as injection molding found its footing, a new invention was poised to transform everything. Coming up in Part 2: A brilliant, bold innovation—the screw injection machine—would unleash injection molding’s full potential, driving explosive growth in plastics manufacturing, reshaping entire industries, and launching humanity into the modern era. Get ready—because the rise of injection molding had just begun.